Horseback in the Andes

A horseback trek in Chile's El Morado National Park, in the Andes just 60 miles from Santiago, with traditional arrieros cowboys and an environmentalist guide

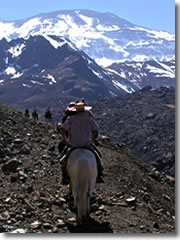

Arriero (Chilean cowboy) guides lead horseback treks through the Andes Mountains on the Chile-Argentina border.

Arriero (Chilean cowboy) guides lead horseback treks through the Andes Mountains on the Chile-Argentina border.

Tomas Alarcon trotted his horse up to ride beside mine and pointed to the vertical layer cake of limestone and shale that rose above the ugly scar of a mining road across the valley.

"I climbed those cliffs when I was a child," said my Chilean guide. "And you know what? There are millions and millions of seashell fossils in the rock. Here, at nearly five thousand meters!"

We rode in silence for a minute, pondering the massive tectonic forces that could lift what was once the bed of the Pacific Ocean more than 16,000 feet above sea level and create the cut-glass peaks of the Andes mountains.

The Road to El Morado

We were only about 60 miles southeast of the capital, Santiago, but a world away from its smog and sprawl. The countryside changed completely an hour outside the city, after our shuttle van passed through San Jose de Maipo, a colonial village established in 1792 to service the area's silver mines and where today daily commuters are slowly edging out local farmers.

From here, we followed the surging, mud-grey Maipo River up an increasingly steep-sided valley between forested pre-Andes, their bald granite pates jagged against clear lapis skies. Tall fingers of cactus scrambled up the riverbanks, and tiny lemon and orange California poppies—called dedal de oro or "gold thimbles" here—fringed the roadside flanked by modern summer homes: faux Tudor, curvaceous Oriental-meets-Gaudí, a defunct diner built as an ersatz ruined Greek temple.

The windows fogged up as glacier-capped Andes appeared at the end of the valley. Forestland grave way to low scrub and lichen-painted rocks occasionally spiked with tall spears of alamos (Freemont cottonwoods), their spade-shaped leaves glowing spring green in the morning sun.

The canyon grew deeper, and I glimpsed a hanging bridge of rope and wood planks thrown across the wild river far below. We passed little shacks advertising onces (Chile's afternoon tea), hand-painted signs hawking the region's famous queso de cabra (goat-milk cheese), and plaster Madonnas blessing roadside streams and watching over driveways from niches in the entrance gates.

Past the tin shanties and rusting storage silo of the defunct gold mining village of El Volcán, fields of snowpack began mingling with the waterfalls spilling off the increasingly tortured and curled strata of rust and charcoal rocks.

Into the Andes

The "tourist information office" in Baños Morales doubles as a horse and guide rental station and an artisans' craft shop—when it's open, that is.

The "tourist information office" in Baños Morales doubles as a horse and guide rental station and an artisans' craft shop—when it's open, that is.

In the village of Baños Morales, built around the thermal springs at the entrance to El Morado National Park, buildings started acquiring the A-line of Alpine roofs.

"We only can make this trip from October to March," said Tomas as the van approached the corral. "In winter, this is all covered in three meters of snow."

We were high into harsh and unforgiving Andes now. Somewhere above us, in 1954, the mummified of an eight-year-old Incan boy with plaited hair was discovered, perfectly preserved after almost 500 years.

We were also about 70 miles north from the spot, made famous in Alive!, where a plane full of Uruguayan rugby players crashed in 1972, the 16 survivors subsisting on the bodies of the dead for more than two months until a pair hiked out and all were rescued. We later learned that, in another valley of the park favored by day-hikers for its easy access to glaciers, a climber had fallen to her death just yesterday.

In short, this was not a place to fool around, and Tomas' company Cascada Expediciones (011-56-2-232 9878, www.cascada.travel; $206 for this one-day horseback ride, multi-day treks available) contracted with local arrieros—Chilean cowboys in flat-topped, broad-brimmed straw hats—to serve as trail guides.

At the corral, the arrieros matched riders to horses: small, sturdy mounts with simple saddles of piled blankets, sheepskins, hair-on hides, even carpet squares. The stirrups were curved booties of leather that resembled hooves.

Felipe Nuñez, only five years old but already a bona fide Chilean arriero (cowboy).

Felipe Nuñez, only five years old but already a bona fide Chilean arriero (cowboy).

I sat atop Canella ("Cinnamon"), a spirited and easily spooked mare who reared when one of the vans' car alarms went off accidentally, and watched a pack of tiny goats hustle across the surrounding boulders. I also paid close attention to five-year-old Felipe Nuñez, the youngest son of our main arriero.

The kid perched atop his saddle in a straw hat and red sweatshirt, feet dangling a foot and a half above the stirrups, expertly maneuvering the horse with a series of vocal clicks and pops, light tugs on the loop of thick rope that served as reins, and the occasional zing of a switch.

Beyond the far side of the corral, massive machines were slowly chewing up a swathe of the cliff face. I imitated Felipe's tongue clicks until I found the one that meant "go," and steered my horse over to Tomas to ask about the open scar in the rock. He didn't know the mineral's name, but we figured it out.

"It is rocks that they cook and make a powder, and that makes the plaster." Ah, a limestone quarry.

Our troop of 30 riders followed a wide gravel path along the Volcano River, threading between jagged mountaintops toward a low sloping dome set against a lapis sky in the distance: Volcán San José, an enormous twin stratovolcano rising to 5,856 meters (19,325 feet) and marking the border with Argentina.

As we turned our horses off the road to clamber up the mountainside, Tomas pointed out an Andean condor circling high above. The horses picked their way between boulders, spooking a few rufus-tailed hawks to take wing. We forded small streams, waded across deep snowdrifts, and clambered up over a low pass to arrive at a high, snow-clad amphitheater of igneous boulders and tumledown granite.

The author astride Canella high in the Andes Mountains of Chile.

The author astride Canella high in the Andes Mountains of Chile.

We got off our horses to admire a panorama of mountains that stretched from the ominous heap of the volcano to our right, all the way around to the El Morado itself on our left—at 5,060 meters (16,698 feet), not as high as some others, but with a jagged Matterhorn-esque pyramid of a peak making it the obvious poster child for the 3,000-hectare park. A few riders scampered off to have a snowball fight.

Enough money can even move a glacier

On our way back down toward the corral—and an outdoor barbecue at the mountain hut of Refugio Lo Valdes (www.rifugiovaldes.com), where gossamer cottonwood seedlings flew through the air like snowfall and drifted into piles against the stacked stone walls —I drew Canella up alongside Tomas to ask him where the dirt road across the valley led.

"To a mine," he said. I expressed some shock that there should be so much mineral extraction going on in a national park. Tomas shrugged. "This is Chile. Mining is what we have."

I had read that Chile was home to the world's largest mine (El Escondida), and had even fought a war in the 1880s with Peru and Bolivia over (among other things) nitrate reserves in the northern Atacama desert.

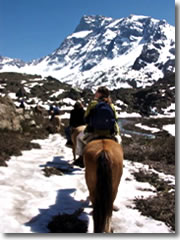

Clambering our horses over this low pass in the Andes suddenly reminded me of the "hero shot" in Lord of the Rings as each of us cleared the gap one-by-one.

Clambering our horses over this low pass in the Andes suddenly reminded me of the "hero shot" in Lord of the Rings as each of us cleared the gap one-by-one.

I also knew that copper is king here, responsible for 45.1% of Chilean exports (just to put that in perspective, the next biggest export—fresh fruit—accounts for 5.3%) and pumping upwards of US$12 billion annually into the GDP. The world gets more than 40% of its copper (and its lithium) from Chile, and mining plays a large role in making Chile one of South America's most prosperous nations. (Chilean copper mines also produce 12 times as much sulfur dioxide pollution as all of U.S. industry combined.)

Still, I was shocked to see evidence of mining simply everywhere we turned, and asked Tomas if it made him nervous that his country's economy was so tied up in one industry. "Oh, it's alright," he said in an ironic tone. "We sell our other natural resources to foreign companies as well!"

"We used to raft the Bio Bio," he said, referring to Chile's most famous river, where the first of six planned dams was completed in 1996. "But now they dammed it." He proceeded to tell me about the plans to sell the rights to a Spanish company to dam two other big Chilean rivers for hydroelectric power—and the fight to try and stop them.

Turns out Tomas only guides horseback, trekking, and rafting trips in the summers, when he's not studying environmental law at Universidad Andrés Bello. He is inspired by the fight over Pascua Lama, a project in the Huasco Valley on the Chile/Argentine border in which Canadian company Barrick Gold plans to move a trio of glaciers to the far side of the mountain so they can get at 17.6 million oz. of gold and silver underneath.

"The environmental department had a report that said it would do not harm to the environment—but that is a lie," said Tomas, pointing out that the glaciers help feed the valley's two rivers, not to mention the fact that the gold extraction will be done in part using sodium cyanide and arsenic—not the friendliest of chemicals.

Our horses ford snowpacks as they climb high into the Andes Mountains of Chile.

Our horses ford snowpacks as they climb high into the Andes Mountains of Chile.

Tomas said, with some satisfaction, that environmental lawyers had managed to put the plans on hold for now because they had discovered that Barrick Gold had paid a local farmer (actually, it was a mining engineer) a mere 10,000 Chilean pesos—about US$19—for all the mining rights, which raised all sorts of legal issues.

Between that mini-scandal, the protests of local farmers, pressure from environmental groups, and questions over the rights of the indigenous Diaguita Indians, the Pascua Lama case is currently tied up in the courts. I asked Tomas if he would finish his studies in time to help stop the damming of the two rivers.

"I will try," he said. "If you cannot stop them, you annoy them with anything so that it makes is too expensive to go forward on the project. That is the strategy."

He paused, looking out over the valley as we rode, at the clear tumbling stream of the Volcano River, and the cruel slash of the mining road through the scree of the opposite slope. Tomas set his mouth in a firm line. "I must do something," he said.

Related Articles |

|

This article was by Reid Bramblett and last updated in December 2011.

All information was accurate at the time.

Copyright © 1998–2013 by Reid Bramblett. Author: Reid Bramblett.