The Smallest Town in the World

In Search of Istria, part 8: An evening in Hum

The main street in Hum is a pretty quiet place.The hamlet of Hum banks on its Guinness Book status as "The Smallest Town in the World," and it is, indeed, pretty tiny: one street, one back alley, a main square, three souvenir shops, and 17 residents packed into a circlet of 16th-century walls under the guard of a tall bell tower, the sides of which were being weeded by a man dangling in a climbing harness.

Still, I've seen crossroads towns in America with fewer buildings, so I asked Aleksandra Rigo, the garrulous owner of the town's newest souvenir stop, the Ethno Shop, what netted Hum the smallest town title.

"It has everything a town requires," she said. "From the Middle Ages it had the prefect—like a mayor—two churches, the council of wiseguys, and the army."

I gently corrected her "wiseguys" to "wise men," explaining the difference in English, and without missing a beat she pointed out that it worked either way, since, "Everywhere, when the government is in issue, there must be a little mafia."

Apparently it was the concept of democratically electing a town mayor that sealed the deal with the Guinness folks, which may explain why Hum revived this old tradition in 1977. A plaque on the little loggia overlooking the main square showed a photograph of the "voting rod," which looked like a half-finished spindle or baluster from a staircase.

"Every June, we pick this guy, who is like the boss for one year," said Aleksandra. "But this is now only a title, nothing else." She grinned. "Still, we have a party, and we drink a lot of biska."

Ah. The biska.

Biska (mistletoe brandy) in just four of its many, many forms.Perhaps I should mention that, throughout our conversation, Aleksandra was keeping up the Istrian tradition of force-feeding visitors shots of the local cordial.

In Hum's case this is a mistletoe-infused herbal rakija called biska that she claims helps lower blood pressure (also inhibitions and, given enough, your entire body to the floor).

The biska she poured me was the sickly yellow of a wolf's eye, its taste an odd combination of bittersweet, sour, and that burning sensation that means you've just destroyed 10,000 brain cells.

"I put in a little honey, because without honey it is too sharp, too like medicine," said Aleksandra as my vision swam briefly. "This is medicine, but why make it ugly? Let's make it beautiful, no?"

I agreed. No shop, restaurant, or roadside stand in Istria will let you escape without sampling its variation on herbed brandy, so I’d already tried a rakija with kopriva (mistletoe). Without the honey, it tastes exactly like that nasty yellow cough syrup you used to get, before the discovery of cherry flavoring.

A sunset dinner of ancient dishes

Dinner with a view at Humska Konoba.I had a sunset dinner on the panoramic terrace of Humska Konoba around the side of the town walls (Hum, tel. +385-(0)52-660-005, www.hum.hr). I dug into a platter of pršut and truffled cheese followed by a bean, corn, and chickpea soup with spicy sausage.

For dessert I couldn't resist the Istriche supa, an "Istrian soup" of mulled red wine poured over toasted bread along with pepper, olive oil, and lots of sugar served in the traditional wide-mouthed ceramic jug.

It was powerful in every sense of the word, and a marvelous throwback to ancient times, when Romans would often toss a piece of charred bread into their red wine (the charcoal softens the wine's acidity). This, incidentally, is why the ritual of raising our glasses and saying a few words at the start of a meal is called "the toast."

Glagolite Alley

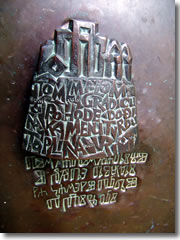

Glagolitic script on the modern gates to HumAs I walked back to my car, a bit tipsy from all the Istrian hospitality, I started thinking about that bit of trivia. I'd long known (and occasionally used at parties) that factoid about the origins of the wine "toast," but had never actually encountered it. I had assumed the practice died out centuries ago. Not so in Croatia, which proudly continues traditions laid down two millennia ago.

But for all the ancient Roman, medieval Venetian, Hapsburgian Teutonic, and modern Slavic influences, Istria is, at heart, not any of those cultures. You could ask locals in what country they were born and, depending on their age, the answer might be Austria, Italy, Yugoslavia, Croatia, or Slovenia. If, however, you simply ask them where they were born, they will reply, "Istria." It is a land unto itself, with its own history and odd charms.

You see this played out on the road to Hum, called Glagolite Alley, where every few hundreds yards there's a gathering of smallish modern sculptures inspired by prehistoric monuments.

Though they look like nothing so much as the woefully undersized Stonehenge prop in This Is Spinal Tap, these are actually an homage to the history of Istrian literature and to Glagolitic script, an alphabet bearing a passing resemblance to Klingon that was developed locally in the 9th century and died out in the 18th century—at least, officially.

When you arrive at Hum, the welcome that greets you, cast into the bronze of the modern town gates, is not Croatian. It is written in Glagolitic. It is Istrian.

Raising one last glass

The story should end there, but Istrian hospitality wasn't about to let me off that easily.

I was almost to my car when I heard the music. Strains of guitar, accordion, and singing were flowing up over the high walls of Hum.

The rehearsal in Hum.Two dozen people had mustered on the main square, singing folk songs and passing around large earthen jugs of biska. As three women got a grill going, the music petered out and the crowd started, apparently, rehearsing a play. The little loggia overlooking the square served as a stage, the stone wall in front of the church an audience gallery.

People seemed to float in and out of the recitation, most of the time tossing what were quite clearly verbal insults at the performers from the peanut gallery sitting along the wall, but occasionally strolling over to take up a role, read a few lines off a script, then return to the wall to sip their biska and crack wise. Some of the performances were wooden, some melodramatic. Many suffered from a biska-induced mumble.

I had no clue what the proceedings meant until someone produced the spindle of power.

In Search of Istria

• Intro - Welcome the farm

• Slovenia's coast

- Piran

- The Soline salt pans

• Croatia's coast

- Poreč

- Rovinj & Limski Canal

- Brijuni National Park

- Pula

• The hilltowns of inland Istria

- Pazin, Motovun, Grožnjan

- Frescoes in Beram & Draguć

- Hum

• Istria Planning FAQ

- Getting to Istria

- Getting around Istria

- Tourism offices in Istria

Ah. They must be rehearsing for the upcoming selection of a new mayor.

I watched for half an hour and never could figure out whom they were planning to elect, but it didn't really matter. I was sitting under the stars on a medieval stone wall in the world's smallest town, with the smell of grilled meat wafting across the square, watching what could charitably be called the world's worst actors keep up an 800 year tradition of democracy.

Then someone passed me the jug of biska.

Perfect.

» On to Istria FAQ: Planning a trip to the Istrian Peninsula

Related Articles |

Outside Resources |

This article was last updated in May, 2009, when a version of it appeared in Budget Travel magazine. All information was accurate at the time.

Copyright © 1998–2010 by Reid Bramblett. Author: Reid Bramblett.

ShareThis

ShareThis